DSC's policy work

To some extent the terms ‘policy’, ‘campaigning’, ‘advocacy’, ‘lobbying’, or ‘public affairs’ can be used interchangeably and may mean different things to different people. They do have distinct meanings, but the distinctions might be unclear for those outside the sometimes narrow world of people who actually do the work or have these words in their job titles.

Historically at DSC, we have generally used the term ‘policy’ or ‘policy and campaigns’ in a broad sense to refer to how we fulfil our charitable objects in the public sphere, in a way that is not directly about delivering services for charities. For reference, our objects are:

‘the advancement of education’

‘the efficiency and efficacy of charities’

These objects are broad and could legitimately be interpreted very in different ways. The work of running training courses, or publishing funding directories, clearly meets these objects. But equally, we have interpreted our public voice, policy work and campaigns as being central to fulfilling these objects too, not ancillary to them. They are about how DSC tries to bring about a better environment for charities to achieve their own ends, whatever those may be.

DSC’s role and style

DSC has always been relatively unique amongst its peers in terms of its business model and public personality in the charity sector. We are not a membership body, so don’t speak for or formally represent other organisations, even though we may work on their behalf. This also means we don’t have a defined group of organisations that might define or prioritise our policy work. We are not beholden to a narrow set of funders or donors to influence our objectives or activity. We have wide charitable objects that don’t overly restrict what we can do.

These attributes are part of what allows DSC to be independent and outspoken when necessary, sometimes saying things that other organisations are unable or reluctant to say. We know from experience and feedback from others that this role is an important and valued part of the mix of approaches, even for those organisations with a quite different style and approach. In fact, at times we have been able to play the ‘good cop, bad cop’, using different styles in coordination with others to influence government.

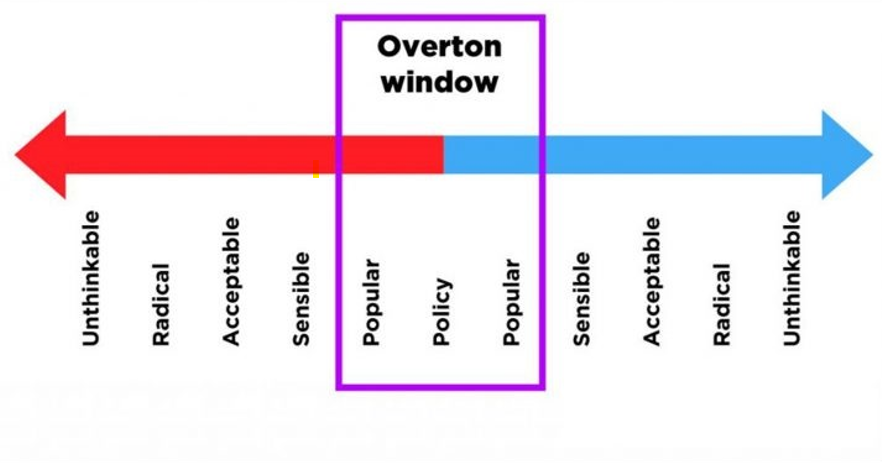

The Overton Window concept is a useful tool to illustrate DSC’s approach to influencing change over the years, referring to a range of potential policies or political agendas that the electorate or general public is willing to accept. The ‘window’ refers to a relatively safe space, or perhaps the status quo. The arrows refer to more radical solutions that may not yet be widely accepted. It can be very difficult to shift the window, either to the right or the left of the political spectrum, without strong leadership, effective messaging, and most importantly without a major event (e.g. a pandemic) or longer-term social changes (e.g. demography) that allow the possibility for new perspectives and solutions to gain traction with the public.

In its own way, in terms of policy for the charity sector, DSC has at times intentionally operated outside the window to expand the scope of possibility and hopefully move the debate in one way or another. This might be by putting out policy demands that might seem unachievable or which are at odds with what seems like a consensus.

DSC’s Policy Principles

In its earlier days DSC’s public positions and style were developed out of the opinions of its founders, most notably Luke Fitzherbert, who pioneered many of our guides to foundations and was a sharp critic of their practices. There was not much of a formal process for deciding what DSC might say or do, and no ‘policy manager’ to organise the work. Luke and his colleagues simply engaged in public debate about issues they thought were important.

As Luke began to retire from the organisation (prior to his tragic death in an accident in 2006), DSC consulted staff and the then trustees to try and codify what DSC stood for. These eventually became the ‘policy principles’, which remain the lens through which we view our public policy work. These ‘principles’ are also accompanied by ‘positions’, which built upon areas that Luke in particular had been an advocate for over many years.

The Policy Principles are outlined in detail here.

Specific Policy Positions

In addition to those principles, there are also some historical areas of activity, or ‘positions’ that DSC is known for, including:

- Charity law and regulation – for several decades DSC has been a prominent voice in debates about the law and regulation affecting charities, trustees, volunteers, and charity governance. We have engaged regularly in Charity Commission consultations and successive Charities Acts.

- Government and the voluntary sector – DSC has engaged in a range of public policy debates about the relationship between the state and the voluntary sector over many years. For example, debates about public service delivery, grants and contracts, the Compact, and the various party manifestos at numerous General Elections.

- Company Giving – In tandem with its unique research for fundraisers, DSC has sought to influence the giving and behaviour of companies who give to or partner with charities to achieve social aims. Often this has been by publishing research or trying to persuade organisations that have an influence over companies’ reporting and transparency.

- The National Lottery – since its inception in the mid-1990s DSC has been a constructive critic of the Lottery, maintaining a position that it should predominantly be demand-led, free of political influence, and deliver grants that are accessible to small charities. We have led campaigns to bolster the Lottery’s independence and to get a Big Lottery Refund from the London 2012 Olympics.

- Trusts and foundations – opening up charitable foundations to greater scrutiny, and advocating for greater transparency about their giving and priorities, was one of DSC’s foundational efforts in the charity sector. In tandem with our research for fundraisers, we have run various campaigns over the years to increase transparency of application processes, criteria and grant conditions.